If a page in Open Office could be ripped out of my computer and tossed in the corner, you wouldn’t be able to see my floor right now. That’s how many times I’ve started this post.

And stopped.

And started again.

This is what happens when an agoraphobic story, desperately wants to be heard, but still isn’t convinced that it’s safe to walk out into the world. No matter how times you dress it up pretty and have it almost coaxed to the door, it may just as easily turn back around, and spend the evening on the couch, with a stale bag of Fritos instead.

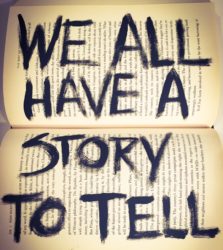

So here’s the thing. Not only do I love stories. I need stories. Even if they never make it outside of my head, they’re my long walk on a stormy beach. They’re my wander through a sun-dappled forest. They’re my Prozac. My Zantac. My Xanax. They’re my prayers for peace and understanding: my arms lifted in gratitude for everything I don’t deserve, but I still, miraculously have; and they’re the unbreakable thread that binds my heart, to the entire rest of the world.

Tell them, and I will listen. Listen, and I will tell them. Put me in an uncomfortable position, and I’ll make stuff up that I probably shouldn’t say out loud. Like when I’m flying. I spend the entire time, with my face buried in a book, blasting 70’s classics or 80’s hair bands through my ear buds as loud as my neighbors can stand it. Then the book and the music, merge into one, and become a story of my own. On my way to Chicago last Fall, entire scenes from Outlander fell victim. Like the one where Claire leaves Jamie in the 17th century at Craig Na Dun. In my vodka spiked version, just as she slips back into 1945, the rocks morph into jumbo versions of those fake stone speakers that they’ve hidden all over Disneyland, like the ones that blast banjo music while you’re having your spine re-arranged on Big Thunder Mountain roller coaster. Then The Scorpions lyrics “Always Somewhere…….Miss you where I’ve been…..I’ll be back, to love you again….” roll into the Scottish countryside as Jamie runs back to fight the battle of Culloden. In red leather pants. And a long auburn perm. With an electric guitar raised in the air. And the battle cry “Je Suit Prest!”. In a voice that sounds exactly like Klaus, as he closed their last set to a sweaty, screaming, half naked crowd in 1989, at Monsters of Rock in Candlestick Park. (Which is an entirely different story on it’s own).

On another flight, a few weeks later, I birthed a Helen Redy /”I Am Woman”/50 Shades of Grey, mutant story-child, that came out looking like a Jim Carrey/Vera-De-Milo/Buffed, Beautiful and Bitch’in version of Anastasia. It talked like me, but with a baritone Vera lisp—and bent Christian’s pinkie back the minute he tried to spank her, and told him if he ever tried it again, she’d rip it off and pin him to the wall, like a bug in a science project, with his fancy leather riding crop. To which he immediately replied “I’m so very sorry. I respect your boundary. Can I buy you a Greek Island in apology?” Then Me/She/We tap our bucky front tooth in thought, and say “No thanks, but a new pair of Manolos would be nice.

“Size 9. Extra Wide. Bunions. You understand.”

Then he looks at us like that’s the hottest thing he’s ever heard, and donates a few million dollars to the Malala Foundation. The End.

In these situation, keeping myself completely distracted until the last bit of turbulence has finally rolled through, is the only goal. Along with making sure that those tiny Matchbox wheels, that have no business supporting the weight of an entire plane, don’t pop off the moment we land, or get ground to smoking nubs before catapulting us end over end.

Yes. Telling stories helps me cope. But these particular ones, and this type of coping have nothing to do with why I’m here.

Which means I’m stalling.

I use stories to do that too.

* * *

It’s been an entire week since I wrote that first part. I’ve caught myself on the verge of Googling “How do I write this damn story?” twice now. Not that it would do me any good. I never find my damn keys that way either. It’s the reason I can go months between posts. It’s not easy to sit in the bug-crawly discomfort of a stage-frighted story, let alone set it free, to run amok, outside the safety of my own person.

As a last resort, I asked Siri.

“What am I afraid of ?!?” I half yelled into my phone, because sometimes it feels good to yell at something that can’t yell back.

“Interesting question, Alyssa” she said in her superior, un-bothered way, and then sent me to an online game, where the pictures you choose, reveal your unconscious fears.

The first time around I got Fear of Death. Not a big revelation. I’m afraid of those creepy clown, pop up music boxes for the very same reason. Knowing the demented clown is coming out of the box, isn’t nearly as scary as not knowing when the demented clown is coming out of the box. So I took it again, and got Fear of Failure.

WA-wa. Disappointed face.

I was hoping for something new. They may as well have told me that I’m afraid of palm sized spiders. Or of accidentally swallowing that placenta-wad, that lurks in the bottom of my Kombucha.

But as I kept scrolling down, it was the obligatory pep talk at the end of the game, that suddenly caught my attention: Many of our greatest fears are unconscious beliefs, attached to untold stories, that may or may not be true. Tell the story. Challenge the meaning. Overcome the fear.

Which weirdly enough, leads me right back here, to the story that wants to be told. About a little girl. And a lost dog. Stuck way back in the recesses of a grown adult’s unconscious mind, creating shadows, and monsters, and limitations, and fears, for no other reason, than she didn’t know it was there.

And of course it’s afraid to come out.

It’s about a little girl.

And a lost dog.

And in the broad scope of childhood trauma, it ranks slightly above falling off the Merry-Go-Round or a badly stubbed toe. Yet here it is, calling daily, with the persistence of a telemarketer who won’t piss off, using every trick it knows to keep you on the phone. “But wait! That’s not all! For just $9.99, your Social Security Number, and the name of your first pet, we’ll include a free set of nose hair clippers!”

Which may be the entire point: Maybe it’s not the bigness, or the smallness of an event that defines the trauma. Maybe it’s defined by the person experiencing it, and their ability to know what they know, and feel what they feel, and to store what they know and feel in a place that they can find it, and name it, and make sense of it. Because when we’re not allowed to know it and feel it, our emotions, and beliefs, get warped and twisted and stuck where we can’t reach them; and before we even realize it, we’ve become a living, breathing legacy, to things that no longer exist.

*ITTY BITTY*

Bitty was my first child. The eat-you-up-adorable Yorkie runt, who was dropped into my world as I held her pregnant mom in my lap. One minute I was watching Donny and Marie, completely conflicted as to whether I was A Lil’ Bit Country, or A Lil’ Bit Rock n’ Roll, and the next minute, I was a new mom, to a blind, grunting ball of black fur and slime. I immediately named her Itty Bitty. Bitty for short. After she opened her eyes and weaned from her mom, she and I were inseparable. She slept with me, rode my horse with me, and shared Shwanz ice cream, straight from the tub, and a jumbo sized Sugar Daddy, as we watched Adam 12 and Emergency 911, under an orange and brown crochet afghan after school. She was Team Johnny too.

Then one day, I came home from school, and Bitty was gone. So were her brother and sister, that we’d named Fat Boy and Fat Girl, because they looked like black and tan sausages, with thick, grub-like tails, that wiggled non-stop. I knew they’d be going to new homes soon, because most of our puppies did, but not my Bitty. I was her Forever Person, and she was my Forever Dog.

No one knew what happened.

Maybe they ran out the door before anyone knew they were gone.

Maybe they’re lost in the woods.

Maybe an owl or an Eagle carried them off.

Maybe they were picked up off the road.

Don’t get your hopes up looking. You’ll probably never see her again.

To a frantic little girl who had just lost her child, all of those possibilities brought unimaginable grief. Every day after school, I walked up and down our old country road, or combed the woods, calling her name. I slept with a picture of the two of us; her on my chest, me with a candy cane in my mouth, while she pulled it from the other end. I saw her in my dreams, hiding under a wet, mossy, rotted log, shivering in the rain.

And crying.

Always crying.

For me.

Her mom.

After not finding a trace of her, on the road, or in the woods, or from the people I showed her picture to at the drug store, or at the market, I knew I would never see her again. The ache in my chest kept me up at night, and when I did go to sleep, that deep feeling of infinite loss, even followed me there. I didn’t speak of her again.

A few months back, I was driving my daughter home from soccer, when we saw a dog in the middle of the road with a massive head and paws and an awkward puppy body. He ran sideways, weaving in and out of traffic, tongue hanging out of his mouth, completely oblivious to the danger he was in. I did a U-Turn in the road and followed him down a side street.

We whistled.

We clapped.

We called down the road in those high pitched, Good-Dog voices, that only pet owners know how to use.

He ignored it all, eventually disappearing into the maze of the neighborhood, and we didn’t see him again.

“If I ever lost Riley, I’d never get over it” said Annika, after we were on our way home again.

Riley is our rescue terrier. Although he’s older than us in dog years, he’s still the baby of the family. My husband is his person, but Annika is a close second. He sleeps on. Or by. But mostly on. Her bed every night. She says she knows what he’s feeling by the twitch of his feet, or the crumple of his ears, and we absolutely believe her.

“Have you ever lost a dog?” She wanted to know.

Thoughts of Bitty, were stashed so far down in my Bank of Things Remembered, they had almost disappeared, so my first response was to say “No”; followed by an ancient ache in my chest—and a painfully reluctant “Yes”.

Then I told her the story of Bitty, with so much detail, color, and emotion, that I actually surprised myself.

She was quiet for awhile, biting her cheek, and glancing out the window, before finally turning to say, “You know you call me Bitty, right? Don’t you think that’s weird?”

Well, of course I knew I called her Bitty. It’s the name I gave her the moment she was laid on my chest, right after she was born. I just didn’t know it had anything to do with my little lost childhood dog. And yes, I suddenly thought it was weird.

If it was a matter of just being weird, I could have stopped right there. Weird and I go way back, and we get along just fine. But it was more than that. What I hadn’t realized, until that very moment, is that a 40 year old story of fear, loss, and grief, had been showing up for an encore performance, in a fully grown woman’s life.

From the time my kids were born, I’ve had a paralyzing fear of losing them. Like on a playground. Or in the store. Or in their own bedroom. I wish I was kidding about that last one, but at least the other two I know are normal. Most parents worry about losing their kids in public. Especially when they’re little. Then as they grow, and learn, and have the ability to protect themselves, and make safe-ish decisions, we as parents, begin to let those fears go.

Unless you were me.

If you were me, you had two teenagers, and still felt inexplicably panicked when they left for school, or walked to a friend’s house, or were in a public rest room for more than 5 minutes. Then in nothing flat, you could escalate from, “Wonder what’s taking so long…” to a vision of lying awake at night, knowing you’d never see them again, completely consumed with unimaginable grief, without ever stopping to consider, the far more likely possibilities in between.

Like hair gel.

Or lip gloss.

Or Snapchat.

Just that day, as I’d been watching Annika play soccer, I found myself searching for her repeatedly. If I didn’t see her familiar run, or the one brown ponytail, in a sea of brown ponytails, that I somehow knew was hers, my hands felt sweaty, and my guts felt jello-y, and my vision felt tunnel-y, and it only went away when I spotted her again. Those feelings had become so familiar, I’d never stopped to question their sanity. They just were.

Except now, I was doing more than question.

That ache in my chest, with it’s nose in the corner for all of these years, was suddenly free from time-out. It was just as painful as I remembered; and for the first time in my adult life, I saw how powerfully present, that decades old story had been.

The ultra-simplified, not-a-professional-so-do-your-own-research-or-get-your-own-therapist, lay-person version, of how this happens, has been explained to me like this: The Conscious part of my brain, that should have been saying logical things like “Of course she’s still on the field. She’s the height of a grown woman, not a teeny, tiny, purse puppy that can disappear without a trace, the minute your head is turned”, was completely oblivious to the story being told by the much deeper, Unconscious part of my brain. This part has no concept of time and place, or even a language of it’s own to say “Pssst! All is well. That terror you’re feeling right now, happened 40 years ago. Relax and Google crock pot meals like everyone else is doing“. Since it can’t tell the difference between what happened then, and what’s happening now, familiar stimuli (like searching for your “lost” child), can cause us to think, feel and experience it, in the same jello-y guts, and tunnel-y vision way. As miserable as that is, the Unconscious brain doesn’t give two hoots about how it makes us feel, because it’s primary job is not to make us happy. It’s first job is ensuring our survival, so it stores events, feelings, emotions and beliefs in a way that it registers as “safe”—even if it keeps us attached to a painful story, in a clearly dysfunctional way.

This is how the memory of Bitty became trapped in a maze of sadness, loss and grief; a repressed sorrow, that was being told and re-told through an invasive, irrational fear. And blocking it’s path to awareness, was a single question, that created so much shame and despair, I’ve spent a lifetime shush-ing it down: “How do 3 expensive dogs, disappear in one day, without anyone knowing where they went?” Even as a little girl, I didn’t believe that no one knew. But by never admitting that I questioned the story, even to myself, I buried the painful possibility, that the god-like people who I trusted the most, may have sold my dog with the other two—which kept the reconciliation of that loss, out of my reach as well.

Our pain hates to be shush-ed. It’s like Glenn Close in Fatal Attraction. “It won’t be ignored!”; and one way or another, it will have it’s say—in either a fully accessible, agreed upon story—Past with Present, Conscious with Unconscious, no boiling bunnies or jacked up hair. Or as an anxious, obnoxious mom, counting heads like Rain Man by the side of the field, or pacing outside of the men’s bathroom and calling “Are you done yet, sweetie?”, to her mortified teenage son.

Every now and then, when I’m at the doctor’s office, and they see that I’m a retired paramedic, they’ll say some version of “Wow. You did that job? I wouldn’t want to do that job. Have you ever needed therapy for all of the bad stuff you must have seen? Here, go pee in this cup”.

Then I respond with some version of “Nope. I’ve needed therapy for everything else, just not that. Do you want a fill job, or just a splash?”.

They look at me out of the corner of their eye, like I’m in some sort of denial or have a trailer full of bodies in my back yard; which sometimes makes me wonder, as I’m shifting in discomfort on that crunchy tissue landing strip, in my gaping floral gown, if I should come up with something else.

“Well, it’s been a struggle, but I do try my best”.

Then we could nod to each other knowingly, with a face that’s appropriately sad, and it would all make perfect sense. But the truth of it is, I don’t struggle. Not because I’m in denial, but because of the exact opposite, I think. Anything sad or mad or painful or gross from the years I spent as a medic, sit in a small, accessible box, on a fully conscious shelf, which means those thoughts, feelings, emotions and beliefs, don’t need to stomp their feet for attention, or get unruly, and misbehave, to be heard. Not the way Bitty did.

When my kids were little, I had a solid reputation as a Grizzly Mom, who most didn’t cross more than once. I did what I knew was right, and didn’t apologize for standing my ground. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. Unless it shows up where it’s not invited.

And it did.

More often than I wanted to admit.

I used to catch people rolling their eyes, or hear them whisper behind their hands—”It must be her job, poor thing……”. Like I had a terminal illness that I wasn’t aware of, and no one wanted to break the news. Being a medic would have been an easy excuse, if I was ever inclined to make one. I do admit, I was way more cautious than most other parents, for pretty obvious reasons. But when rational concern, turned into scary monsters that I couldn’t explain, I knew it wasn’t “my job“—I simply had nothing else to call it at the time.

In all of the years I spent doing what many would call a traumatic job, I only carry a handful of calls with me, and even fewer names and faces. Not because they didn’t matter, but because they did; and one way or another, they were laid to rest instead of being left to wander, like homeless ghosts in the door wells of my mind. Do you know what I do carry with me though? The way the ambulance smells in different weather; like oil, metal and pavement when it’s hot, and like a big, un-bathed rodent when it’s wet. And the weight of our block radio, as it hung from my peeling leather belt. And the grid of the city, like a GPS tattoo, etched into my brain. And the cloudy scratched plastic, blurring the buttons on the Lifepack, like a kid’s candy fingerprints. And the clunky laptop, pulling on my shoulder, as I lift it to write a chart. And the smell of 7-11 Nachos after being stuck for twelve hours, under the drivers seat. And the taste of a lukewarm Venti coffee, with chunky swirls of Half and Half, floating on the top. And the way my waffle bottom boots squeak when they’re wet, across the shiny ER floor. And the early years of Fail-Safe, blaring in our ears, when we took a corner over 40 miles per hour. And the bare dangling wires, when my angry lead ripped it off the wall, and threw it out the window. And the laughter of my favorite partners. Or which ones snore. Or who would only eat a one kind of Pad Thai, from one single booth down at Saturday Market. And who would eat anything, from a withered carrot found rolling on the cab floor, to a day old McRib, left in their work bag overnight. And the pure fun of driving code 3, especially when it’s dark. But there are no pop up surprises. No painful stories left unresolved. Nothing forgotten that should be remembered. Nothing remembered that I should forget. Which is my best explanation, for why a big traumatic job, left a much smaller imprint, than my black and tan Yorkie runt.

The events in our lives are funny that way. Whether we know it or not, they’re constantly weaving a fabric. When we can feel what we feel, and know what we know, the threads become part of a strong, resilient whole. But the ones we snip back, (or that are snipped back for us through shame, guilt or fear), are fragile, and weak and eventually leave a hole. The hole that’s left, becomes the untold stories that live on and on, through our destructive thoughts and behaviors, our liming fears and beliefs, our unexplained anger and control issues, our self-sabotage, addictions and relationship failures—and so much more. Like a highly anxious mom, who doesn’t know she believes, that her two beloved children are destined to disappear, like her beloved childhood dog.

I’ve always said that I became a medic because it’s fun. You learn real quick (like after you’re slapped down on your first ambulance ride-along), to never say “because I like to help people”. But it’s ok to say it’s fun. And for more reasons that I have room to explain, it really was fun. But on a deeper, and yes, unconscious level, I know it gave a voice to some very different stories, that I also couldn’t tell out loud. Like chaos. And abandonment. And betrayal. And unimaginable loss. And being taught to believe that I was a disgusting, worthless, un-savable worm who was hated by God. And a crippling fear of death (For obvious reasons. Like burning in hell forever.Duh.)

If fear, anxiety, worthlessness, and visions of being flung into the pit of hell by a laughing, vengeful, god-monster was the disease, being a medic was the cure. When I entered that realm, I felt indescribable peace and calm, because when other people were depending on me, fear and anxiety lost their power. There were tools. There was a plan. There was a way to control the chaos that usually seemed to work; and when it didn’t, I knew, that the dying aspect of living, was completely out of my hands. I hadn’t caused it, or created it. I was only there to help. And someday do something so heroic, that god would forget that he hated me. And hopefully pay my penance for being a disgusting, worthless, un-savable worm.

I ended my career, never feeling like I succeeded in that, but the one thing I did understand: in allowing me to tell my story in a way that my soul understood, it’s my patients who really saved me, instead of the other way around.

You know that saying, “When the past comes calling, don’t answer it. It has nothing new to say”? Well I think it’s exactly the opposite. When the past comes calling ANSWER THE DAMN THING. And then invite it over for coffee; and ask it to tell you everything it knows; and then tell it everything you know; and then keep inviting it over until the conversation becomes so incredibly boring, it doesn’t want to talk to you anymore.

Because here’s the thing. Dealing with our past isn’t like removing a tumor, where the bad part is cut away, and the good part gets to stay. The good and the bad are fully intertwined, and in shunning our past to escape the bad, we lose the rest of our lives as well. In knowing what we know (even if that means shaking your fist at no one, and screaming into the air “You sold my eff-ing dog?!?), and feeling what we feel (even if it means ancient tears, streaming down your face, that you haven’t tasted in 40 years); we not only preserve the fabric, but we create new fibers of meaning and belief, that weave in and out, through time and repetition, to eventually mend that hole.

“Letting go” doesn’t mean spinning around an ice castle, singing a Disney song. If we really want to let something go, we have to pick it up, first. That means facing our stories, grabbing them tight, holding them close, listening to what they’re saying, over and over, like a child who’s afraid of the dark, until we fully understand; and then, and only then, can we truly set them down. Feelings from our past, don’t go away, just because they don’t make sense in our present lives. Neither do the holes from the stories we’ve left untold. We may call it choice, or destiny, or being cursed, or “this is how I’ve always been” or “I don’t know why I feel like this but…”, or “how do these same things keep happening?”, when the truth of the matter is, it may just be an Itty Bitty story, that’s so desperate to be heard, it does whatever it thinks it has to do, to simply be invited in.